Notes on 'Grunge'

Grunge photographer Charles Peterson and I chatted about grunge’s legacy as the ‘Last Great Music Movement Pre-Internet’ in an effort to understand Seattle’s fashion and music scene.

Londoners are chic. It seems that the city effortlessly rises early, purchasing their morning coffees in a Burberry trench before catching the tube to work at, oh, maybe a PR firm, maybe even a British Vogue office. While living in London this fall and, admittedly, discussing my gripes with the almost nonexistent Seattle fashion scene, I was asked on multiple occasions: “But people must dress cool in Seattle, right? Isn’t it, like, the home of grunge?”

Sure, Seattleites dress cool. We wake up at a convenient time, put on some sweat pants or enormous jeans, definitely purchase a coffee, then go rock climbing in between working from home. But Seattle isn’t chic, doesn’t have that je ne sais quoi that Londoners possesses. We’re not cohesive, we don’t show up as a polished unit to catch the morning train to work.

Seattle is a geographically isolated city with subpar weather which, prior to grunge’s popularization in the late 1980s, wasn’t remotely on the map for touring musicians, and certainly wasn’t considered cool or fashionable. In the late 80s to early 90s, riddled with economic hardship in the wake of two recessions, Seattleites tore through Goodwill racks to assemble an outfit inspired by photos of The Cure, trends from Vogue, or something they saw Bikini Kill wearing at a show. Music lovers, including a young Kurt Cobain, assembled and adored their record collections which, for Kurt, featured a hodgepodge of cheap Beatles, REO Speedwagon, and Melvins records. Seattle didn’t have an identity of its own, a music genre or style to claim, until grunge was formed from an adoration of pop culture and a lack of access.

So, grunge—what is it?

“Grunge is dirt, it's scum, it's a descriptive word that’s used to describe just raspy sounding rock,” Mark Arm, lead singer of Green River and MudHoney, said in a VH1 Grunge News Special.

Legend has it, ‘grunge’ was coined in the late 1980s by Arm, who was quoted in “Loser: The Real Seattle Music Story” describing his own band as “Pure grunge! Pure noise! Pure shit!” Grunge was later popularized by Bruce Pavitt of local record label Sub Pop when describing a single by Green River—although speculation remains over where and when the term technically came about.

Photographer Charles Peterson thinks his old roommate at the University of Washington, Mark Arm, picked up the term from reading Lester Bangs, a music review critic for Rolling Stone and Creem Magazine.

Charles Peterson was at the forefront of grunge, initially by documenting early grunge bands Green River, the U Men, and Metropolis in the early to mid 80s, alongside touring bands like Black Flag, the Meat Puppets and Dead Kennedys. Peterson would later photograph some of grunge’s most referenced photos, from Kurt Cobain wearing a hospital gown at Reading Festival (and the live album cover) to Soundgarden’s album cover for “Louder than Love.” Peterson’s photos for Sub Pop 200’s vinyl album, including a 20-page booklet packed with concert photos of Nirvana, Mudhoney and Soundgarden, transported grunge from a local phenomenon to global sensation.

Despite its popularity, grunge as a term was initially rejected by these bands, wanting to be a part of their own distinct sound rather than grouped together for the purpose of selling a movement.

“At first we kind of used [grunge] as self-deprecating, to a degree,” Peterson said. “A bit later on we kind of had to reject it and then now it's kind of come full circle where we totally embrace it again because how else are you going to really describe the movement or categorize it…Pearl Jam is entirely different band from Mud Honey, and Alice in Chains is entirely different from Tad, and yet here they were being all lumped under the grunge umbrella.”

I caught up with Peterson to unpack his experience photographing the scene before—and after—its international success, and his take on grunge’s legacy in Seattle today.

“My intention was to set out and try and take the best live photograph ever,” Peterson said. “Or at least put my spin on it.”

Due to strong marketing tactics, largely on Sub Pop’s behalf, the image of grunge sold, and it sold fast. This included its fashion identity; a distressed denim, frayed sweater, flannel and Dr. Martens kind of vignette.

To say the scene reached rapid, and ever-present, mainstream fame would be an understatement. Today Vogue’s website lists 752 stories about ‘grunge,’ ranging from ‘Kristen Stewart’s New Hair is the Grunge Version of Princess Diana’s Famous Cut’ to ‘The Teenage Dirtbag Sweater is my New Fall Staple.’

“So many people were trying to cash in on [grunge],” Peterson said. “From fashion designers to bands moving in from out of town, etc. That really had no cache in our minds.”

This statement rang true throughout the 1990s, as designers like Anna Sui, Christian Francis Roth, and Marc Jacobs for Perry Ellis—a collection that had been re-released in 2018 despite its controversy in the 90’s—pulled direct inspiration from Seattle’s grunge scene, even earning Marc Jacobs the title of a ‘grunge connoisseur’ (he had never been to Seattle).

The inspiration for these runway shows existed almost exclusively in the basements of Seattle, small stageless record shops and dive bars, and the fraternity houses of the University of Washington and Evergreen College in Olympia.

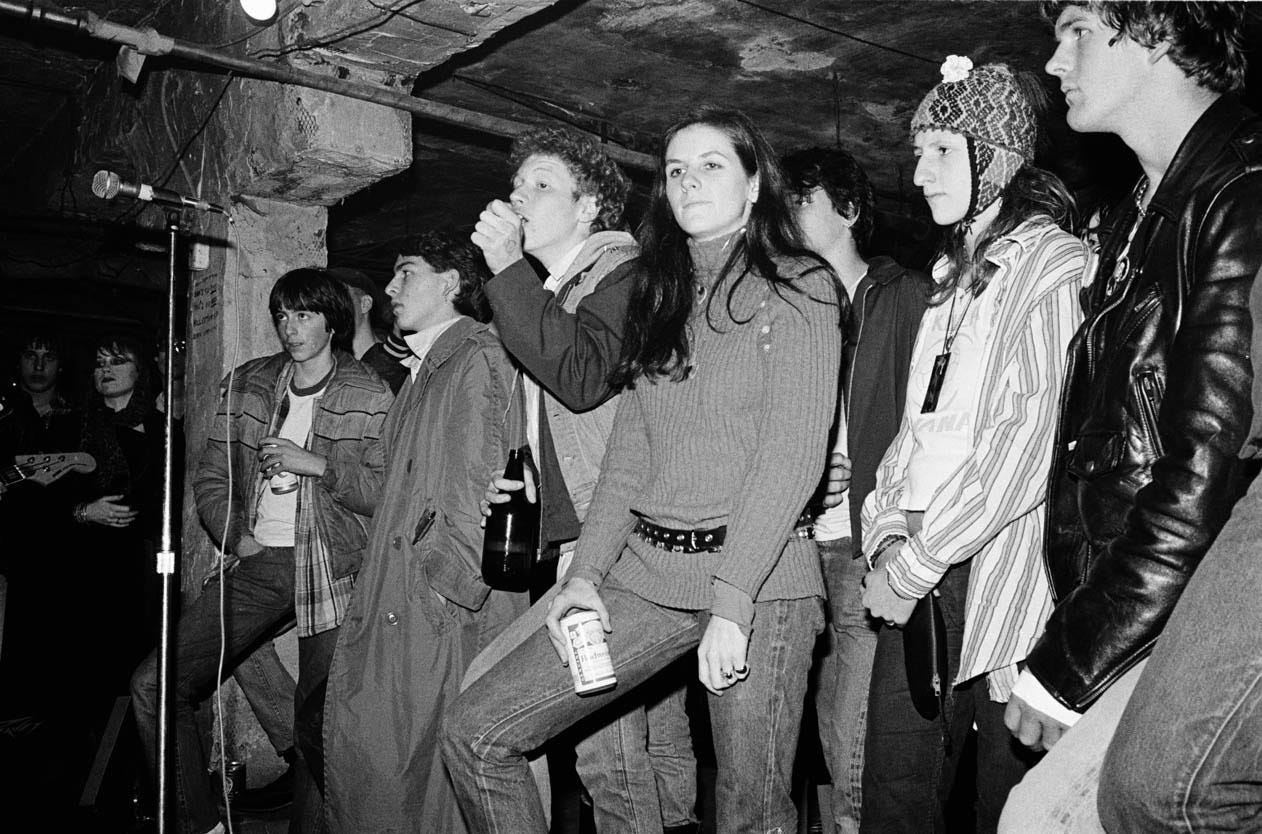

Peterson recalled a photo he took in a ‘cruddy basement’ at Graven Image in Pioneer Square as Ten Minute Warning, a hardcore-punk Seattle band, played.

“I included [the photo] in my book, Touch Me, I'm Sick, and my designer and I would refer to that image as the stray dog from every village. Because in the lineup, you had one girl that kind of looked hippie, another looked goth, another guy that had like the punk leather jacket on, another guy that was sort of starting to wear flannel, one kid with like, an overcoat. It was sort of like everyone was just bringing their own thing to it.”

Grunge occurred at a time of heightened individuality post-recession. Finding a niche through music, art, or fashion to subvert one’s interest and establish identity felt imperative. Kurt Cobain was a connoisseur of crafting his grunge-rockstar image, creating Nirvana’s early album art, wearing vintage slip dresses or hospital gowns to perform live, and even inventing a persona, Kurdt, to embody the edgy, disruptive, confrontational version of a person who was notably quite shy and awkward.

Much like Kurdt’s costumes and alter-ego, grunge was used to promote a fictitious dream of the movement rather than a reality of financially fraught youth. I don’t say this to be critical, I think the reality is simply much more interesting and long-lasting than the flannel fantasy: youth were honing their personal style sensibilities in a city isolated from the larger fashion conversation taking place pre-internet. This meant disjointed, at times lumberjack-esque garments paired with goth, Robert Smith-inspired eye makeup. Perhaps ‘grunge’ isn’t an accurate descriptor for the fashion scene then, or now, but instead fashionable, earnest discombobulation.

I thought about this while sitting at Linda’s Tavern, a cowboy-themed bar in Capitol Hill nicknamed the ‘Grunge Cheers,’ once frequented by grunge musicians and complete with a metal/punk-rock/grunge jukebox, mounted taxidermy and a deer hunting game—the grunge aesthetic has no limits.

“I just never really thought about fashion, period. I still don't,” Peterson said. “For me, it was more just interesting [seeing] the way the band and audience would interact.”

After all, the music and live shows were grunge’s core; post-punk, muddy, distorted guitar compounded by heavily emotive, honest, even poetic lyrics.

“I think that the punk influence to grunge was really only more in idealization versus the way they made the music,” Peterson said. “A lot of us came out of the punk days and the punk movement…but also realize that it was a little bit of a dead end. I'm a huge punk fan, and it's always been near and dear to my heart. But I think that musically the grunge bands wanted to kind of go beyond that…You could do fast and slow parts [with Grunge].”

Perhaps a bigger influence than the music genres themselves were the all-encompassing vinyl collections.

“Mark Arm and I, when we were hanging…pre-MudHoney, pre-Green River, we would put on a Black Flag album and then we'd put on a Can album and then we put on a Brian Eno album. We just were into music. It wasn't necessarily like, yes, we’re only gonna listen to punk because that's all that matters,” Peterson said.

Peterson indicated that his favorite band out of last year, British band Yard Act, demonstrated an ever-present need for record collecting to diversify a band’s sound, as audible Gang of Four and Sleaford Mods inspiration led him to believe the band must have a ‘pretty killer record collection.’ For this reason, Peterson stated:

“[Grunge] really was kind of the last great musical movement, I mean particularly before the internet, before everything became homogenized and globalized to a degree.”

I asked Peterson if he ever met his personal goal of capturing the best live photograph ever.

“I will say I don’t believe in absolutes,” Peterson said. “But when I took the photo that ended up being the cover for Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love album, it was when I knew that I was doing something truly unique, and had at least accomplished my personal goal. Of course there were others before, and even more better after, but that was the first time I knew I had taken an image that would stand the test of time and was unlike anything that anyone else was doing or had done.”

Post-grunge, Peterson began pursuing a new stage for his photography in the early 2000s: breakdancing.

“It was a really refreshing change because it was sort of like, oh, I just go down the War Room and pay my $5 entry and go take pictures all night, and there were no managers or publicists or all that bullshit to deal with,” Peterson said. “[It was] super refreshing and sort of reminded me of the early days of grunge.”

The ability for everything; hip-hop, breakdancing, punk, grunge, to coexist cements Seattle’s indefinite future as a hub of miscellaneous, boundaryless subculture.

It seems this lack of cohesion in Seattle is what put the city on the map, in the first place. We can thank grunge for the access it has provided Seattle in terms of live music and fashion, however maybe Seattle doesn’t, and never did, fit into the parameters of ‘grunge.’ Maybe it goes beyond that, a city moved to experiment with their wardrobes and music collections on an individual, trendless level, ultimately crafted around personal and accessible interests. You can have your coffee and go rock climbing, too.

Fantastic read!