McQueen on Display: What Makes a Good Fashion Exhibition?

After speaking with Simon Ungless about the stories behind the Alexander McQueen pieces featured at The MET, it became clear that it’s the stories behind the garments that revive them, not technology.

How can you make a garment emotionally moving when it can no longer be worn? It seems that’s the question The MET’s Costume Institute tried answering with “Sleeping Beauties,” their most recent annual MET Gala exhibition—upon visiting, viewers can view, smell, ‘touch’ (a 3D-printed miniature recreation of the “Miss Dior” gown) garments that are too delicate to be worn again.

It’s nearing the end of summer, the peak of a museum’s attendance, and as we’ve traveled, or watched our friends travel on social media, fashion exhibitions such as The MET’s “Sleeping Beauties,” the De Young’s “Fashioning San Francisco” and the traveling show “Lee Alexander McQueen & Ann Ray: Rendez-Vous” have been available for our viewing pleasure. Viewers can now try on couture gowns via AI generated imagery, and snap a mirror pic for Instagram while doing so.

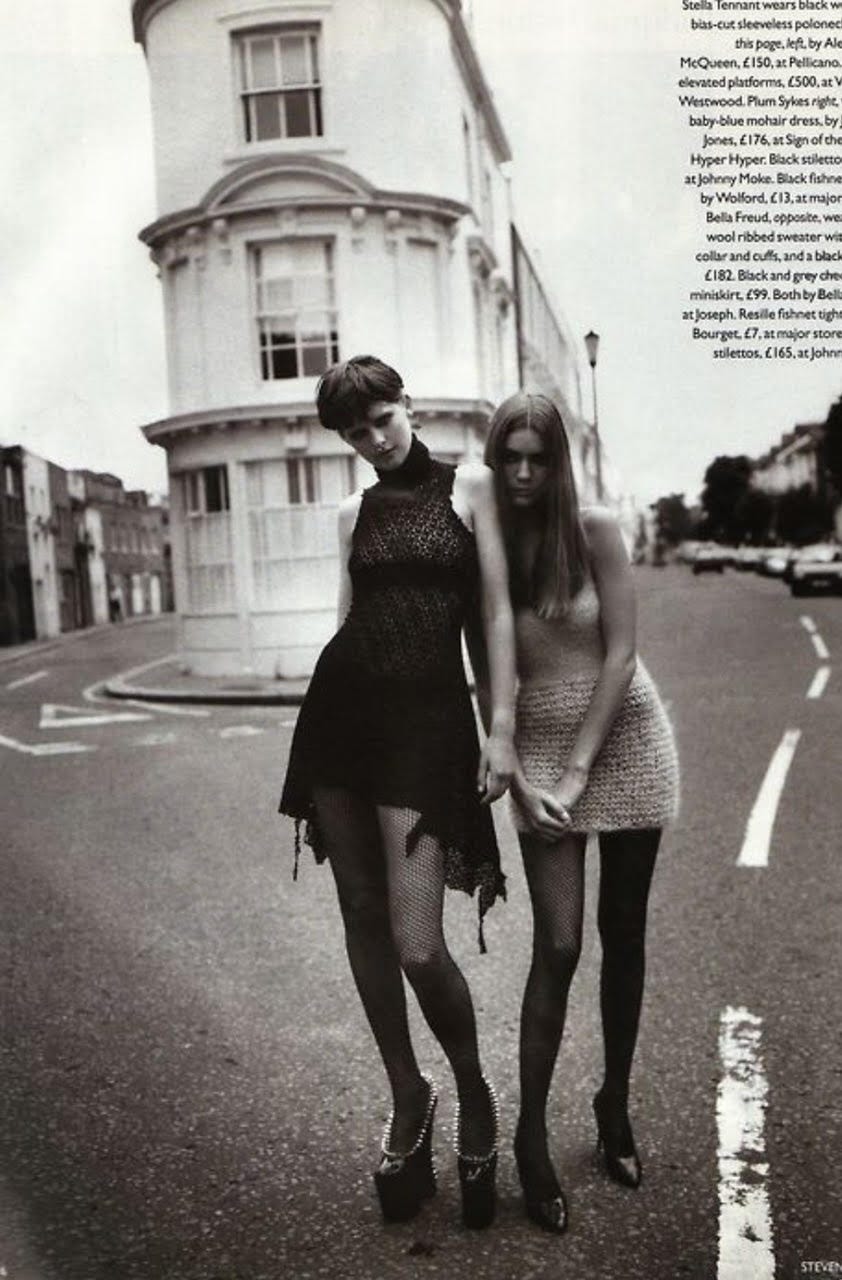

But it’s walking through an exhibition, like “Fashioning San Francisco” at the De Young, and observing that many of the 100+ garments belonged to one woman: Georgette Barbara “Dodie” Rosekrans—one outfit, a draped Comme des Garçons tartan skirt paired with a revealing John Galliano blazer with arm cutouts, she wore at age 87. It’s scrolling through Instagram and viewing a sharp, tailored orange Alexander McQueen blazer, swallowed by a print of birds and laid flat under glass at The MET, then seeing it strut down the runway on Vogue writer Plum Sykes on the next slide. I feel it’s the stories behind garments that bring them to life; the context that awakens these sleeping beauties, not gimmickry often posed by technology.

Each of these exhibitions feature delicate hallmarks of the Alexander McQueen brand, pieces created in collaboration with Simon Ungless who printed patterns and created textiles for the brand’s early collections, or Sarah Burton who preserved the brand’s legacy and enhanced it’s femininity following “Lee” Alexander McQueen’s death in 2010. Each exhibition proved that even when the garments are exemplary on their own, context and sincerity revive them further.

For Simon Ungless, a designer, printmaker and original member of the Alexander McQueen team, creating clothing was nothing short of sincere; a culmination of inspiration—his Central Saint Martins summer project inspired by tartans and early Scottish clans, which initially drew fellow student McQueen to Ungless. A feat of budgeting, as the pair utilized affordable materials, leading them to innovate with manipulations of latex, plastics intended for credit cards or shampoo bottles, even hair. Design was an earnest, inspired, grueling and at times impulsive process—Lee would spend days tailoring a dress and after its completion ask Simon to “go fuck it up a little.”

Ungless and I chatted as he sat at his printing table double-functioning as a desk; a “huge piece of glass, [that he would smear] liquid latex all over.” In the early years of the McQueen brand, Ungless realized he “could make my own sheets of latex. And so you let it dry, peel it off, and you create your own. And then I would sprinkle feathers into it or hair or all this stuff and we'd make fabric that way. And then Lee would just drape it on the form and it’d become a top or a dress.”

Latex became a recurring material for the brand, used to make a dress for Stella Tennant’s first Vogue shoot with Steven Meisel. Roommates at the time, the pair bought a knit lace jersey fabric, Lee draped the material on Simon, and then asked him to hem it.

“I had to say, no, I'm not going to,” Ungless said. “And I dipped the edge into latex and it completely sealed it. And he was just like, ‘Oh my God, that's amazing. I love it.’ I was just like, well, that's what I did in my undergraduate—cause I was lazy. I didn't wanna sew.”

The pair continued to using latex and plastics, such as shower curtains from B&Q, leading into their preparation for the 1994 collection “Nihilism.”

“During that process, I was out in the backyard, there was a huge drain cover. And I ran out the back door and I kicked the latex over into the drain cover, which was annoying because it was our last one and we were broke. And then we just started sprinkling glitter into it and let it dry, and then peeled it out. And it had kind of created a mold of the drain cover. And then we did glitter and feathers and leaves, and draped it, and it became the top of a dress, we laid fabric into it. And then when it peeled out, it kind of almost looked like a bodice shape…so it was being resourceful and letting accidents happen. I've always loved that.”

At The MET, two avian inspired Alexander McQueen blazers lay under glass for “Sleeping Beauties,” too fragile to be worn again due to age and exclusivity—the orange jacket from “The Birds” was the only one ever produced. A shadowy projection of swallows swarm overhead, evoking imagery from Hitchcock’s homonymous film, the inspiration for the S/S 1995 collection.

Both bird watchers in their youth, the pair referred to Ungless’s bird spotting books he kept at their shared apartment in Tooting—the Observer Pocket Guide to Bird Watching, while brainstorming for the collection.

“Each page has a picture of the bird, information, and then at the bottom, there's it’s flight pattern,” Ungless said. “And Lee, looking at it, said, ‘That's what I want, that's perfect.’ And he picked garden birds. There was like a sparrow, a robin, and I remember saying to him, ‘you know, I don't think those birds feel very threatening.’”

Ungless made the print with robins in a swarm-like pattern similar to the finalized print.

“When I printed it, I was just like, ‘Oh my God, it looks like a really bad Christmas card,” Ungless said. “Like, the worst Christmas card ever.”

With the help of McQueen’s partner at the time, Andrew Groves, Ungless printed a combination of swifts, house martins and swallows two days before the show, effectively creating the collection’s most recognizable piece.

The collection echoed this experimentation with material, utilizing “this thing called foil,” Ungless said. “They're not designed for fabric. They, at that point were designed for plastic…they print them for credit cards and shampoo bottles. So I worked out a way that I could laminate fabrics, lace and different things. So when those garments went down the runway, it was literally the cheapest lace fabric I could find—printed, laminated, went down the runway, and people went crazy because they'd never seen anything like it before.”

The second jacket featured at The MET—a black blazer printed with feathers from the S/S 1996 collection “The Hunger,” based on a vampire film with David Bowie—is another sleeping beauty, this time due to wear. Its owner, McQueen’s first employee Trino Verkade, wore it so much that it began to crack. Feathers weren’t unfamiliar to Ungless, who sat with McQueen and made feather shapes out of beaded fabric, shredded them and then sewed them to create a textured fabric for his Central Saint Martins collection.

“[In ‘The Hunger’] there's a scene towards the end where there's all the pigeons or doves flying around them,” Ungless said. “At the time, you don’t think about building recognizable brand notes that continue through the collection, but that was obviously what that was doing.”

Ungless created the print from jackdaw feathers, a smaller crow in the UK, laying them on a nylon silkscreen coated with a light-sensitive emulsion to print the image. Additional prints for the collection consisted of hawthorn branches printed onto shower curtains, another motif for the brand and featured in Lana Del Rey’s McQueen Met Gala look this year.

“Those pieces were not done in Italy,” Ungless said. “They were done by me in London. Not really meant for production because, you know, that's part of telling the story.”

Bird imagery continued throughout McQueen’s work and was persevered after his death. Successor Sarah Burton, who was introduced to McQueen by Ungless as his student at Central Saint Martins, carried on his legacy. A monarch butterfly dress in The MET comes to mind, made by Burton for her first collection at the brand following Lee’s death, constructed entirely of hand-painted turkey feathers.

“What's really important to me [about that collection] is some of the tailoring, where she took layers of chiffon, and tailored it so that it was still McQueen's silhouette but because of the nature of the fabric, the clothes became so soft and wearable but still kept the silhouette. Incredibly brave, incredibly intelligent woman and very loyal and passionate about her years with McQueen and Lee,” Ungless said. “When Lee passed away, I think there were three stores. When Sarah left the company, it was something like 200…Sarah brought a lot more beauty and softness and accessibility to the collection.”

Alexander McQueen shows were performative, theatrical even, but not gimmicks, not primed for social media, but for Ann Ray to photograph, or Plum Sykes to write about after walking in “The Birds.”

As we’ve seen over the past few years, with Coperni’s spray-on-Bella-Hadid dress for example, described by some as a less innovative version of Alexander McQueen’s Spring 1999 show featuring Shalom Harlow spray painted on the runway, fashion gimmickry is abundant, crystal clear even, in nearly all facets of fashion today. Writer Rachel Tashjian stated with McQueen’s collection “there was wonder and delight. Coperni's effort was vaguely scientific.” I think this is why the Met’s “Sleeping Beauties” fell flat; smelling an old victorian garment, touching a 3D-printed lace textile, trying on a CGI gown—it all feels like a mundane feat of technology. There was a hologram at The MET: an animation of a victorian ballgown on a faceless, mannequin-like figure, the wearer and designer unknown. Alexander McQueen’s 2006 show “Widows of Culloden” comes to mind, ending with a floating hologram of Kate Moss wearing a windblown sheer gown from the collection. It takes a supermodel, or any person, really, to animate a collection to such a degree. And with The MET’s budget—the museum reportedly made $136.2M in 2023, one would hope the same efforts could be made.

It’s the personal touch, the faces to these garments, that I feel museums often lack. In a recent interview with Liana Satenstein, Plum Sykes claimed when writing her pieces for Vogue, “The girl in the dress was more exciting to me than just the dress on its own.”

For the late Georgette Barbara “Dodie” Rosekrans (1919-2010), a San Francisco socialite and John Galliano’s first couture client, her closet proved sheer commitment to even the most impractical couture; she was remembered attending dinner in a Jean Paul Gaultier jacket with feathers nearly engulfing her hands, a piece on view at the De Young, alongside dozens of other items from her closet. I did this research at home, but how interesting to have had her picture or life story displayed with her clothing?

Also featured in “Fashioning San Francisco” is a black layered gown from Karl Lagerfeld’s first collection for Chanel purchased for the opening night of the San Francisco Opera in 1988—how fabulous. Fashion is at it’s best when it’s earnest; in a closet, on the runway, and especially in a museum.

It’s these closets of collectors that allow for some of the most memorable museum moments, anyways. Fabulous people who purchased the clothing for themselves and preserved them.

Ungless traveled to Nashville last month to view “Lee Alexander McQueen & Ann Ray: Rendez-Vous,” specifically a certain dress he wanted to be reunited with.

“There was a dress I worked on for Lee for ‘Highland Rape’ [A/W 1995]. Again, using latex onto fabric, draping very quick, just for the show,” Ungless said. “You know, I never really thought about that dress ever again. It was all ripped and whatever. It was just part of a runway; a hit them over the head with the inspiration story. Somehow that dress ended up in the ownership of a woman, and she had that hidden in the back of her closet for 25 years. She sold it relatively recently.”

Due to the dress’s fragility and creation exclusively for the runway, Ungless felt it would have been his first pick for the “Sleeping Beauties” Met theme. The “Rendez-Vous” exhibition features runway pieces from early Alexander McQueen years, contextualized with photos taken by Lee’s friend, Ann Ray.

This fashion history context is what makes these pieces memorable, in the first place. Kendall Jenner’s gown at the Met Gala, a Givenchy by Alexander McQueen piece was noteworthy because of its designer and the story behind it: the gown had never been worn before, as it was shown on a mannequin for the 1999 presentation. Context makes news.

So why is this so hard for museums to grasp?

Another McQueen piece at the De Young consists of a suit printed with gold florals from McQueen’s “Dante” collection in 1996, crediting Ungless’s print work on the placard. Simon also holds onto a piece from this collection, one hidden from the public.

“I have two things from Dante that shouldn't exist,” Ungless said. “It's one of the photographic prints of Don McCullin's photography that we used for inspiration for the show, and in our enthusiasm and in our youth and our naivety, we didn't seek permission to use his pictures. When he saw them, when his agents saw them, they tried to sue us for use of his imagery…I mean, we just didn't know any better. So everything—screens, transparency, garments, all had to be destroyed. But I kept a top and I kept a strike off of the fabric, the first print I did.”

Some things are meant for the back of the closet, but most times those garments make the best exhibitions—if only their stories were more thoroughly told. Today, Ungless designs for his own brand, When Simon Met Ralph, and has partnered with Atelier Jolie in an effort to restore preloved garments through screenprinting and sustainable alteration. Based on the other garments he’s worked on, I’d assume they’ll be museum quality one day, too—after being dug out of a fabulous San Franciscan’s closet, of course.